“Those who take pleasure in the accidental beauty of poverty and historical decay, those of us who see the picturesque in ruins — invariably, we’re people who come from the outside”.

Orhan Pamuk '’Istanbul: Memories and the City’

If you come from one of the tidier countries of northern Europe, like the UK, then you will spend the first couple of days of your first visit to Ayvalik in a state of shock. The guidebooks will have told you of the charm of the town’s cobbled streets, lined with picturesque old Ottoman Greek houses, and you may well have had your appetite further whetted by the ‘Rough Guide to Turkey’ rhapsodising thus:

‘Ayvalik presents the spectacle –almost unique in the Aegean – of an almost perfectly preserved Ottoman Greek market town, its essential nature little changed despite the inroads of commercialization. Riotously painted horse-carts clatter through the cobbled bazaar, past the occasional bakery boy roaming the alleys in the early morning selling fresh bread and cakes….

There’s little point in asking directions: use the minarets as landmarks and give yourself over to the pleasure of wandering under numerous wrought-iron window grilles and past ornately carved doorways.’

Well, yes -

- a whole book could be devoted solely to the eccentric beauty of the doorways and wrought iron work of Ayvalik .

But what they don’t tell you about is the ruins.

In an earlier post I described how in September 1922 the Orthodox Greek inhabitants of Ayvalik were forced to leave the town and migrate to Greece, taking with them only what they could carry, and how they were replaced a year later by Muslims forced to migrate in the other direction, from Greece to Turkey, who moved into the abandoned houses of those who had left, and turned their churches into mosques.

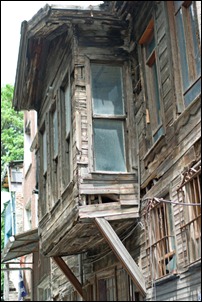

The incoming migrants, however, were much fewer in number than those who were forced to leave, which meant that a lot of houses were left empty. Some of them have remained uninhabited to this day, and have been standing there, slowly decaying, for the last 88 years. This process was accelerated by an earthquake during the 1940s, during which some of the taller, three- storied houses lost their upper floors. As a result, the charming cobbled streets of Ayvalik feature - amongst the moderate number of houses that have been properly restored and the rather larger number that have been modernised in what is perhaps best described as an ad hoc fashion – many houses in various stages of decay and ruin, some long beyond the hope of repair.

My street contains several beautifully restored houses, amongst them the elegant summer residence of one of Turkey’s most famous rock stars (the house and its restoration have been featured in newspaper and magazine articles in Turkey, so its location is well known):

It also, in rather marked contrast, contains this

and, right next door to me, this:

The ruins are beautiful in a heartbreaking kind of way: you will see a huge, imposing doorway (Ayvalik is full of doorways with attitude), a magnificent facade, and behind it nothing…

…but the bare bones of the house it was once was.

Houses fall down regularly in Ayvalik, despite the fact that the old town is a conservation area, and has been for decades; a friend of mine narrowly missed being hit by the falling rubble when the house pictured below collapsed a few months ago:

To someone coming from a country whose architectural heritage is preserved, conserved, restored and polished to the nth degree, such a state of affairs is, at first, literally incomprehensible. The first-time British visitor wanders about the old town of Ayvalik dazed and confused: delighted by the beauty of the town, but simultaneously quite overwhelmed by the stunning visual impact of its decay.

It takes a bit of getting used to.

Once coherent thought returns, the visitor’s next reaction is ‘But this is terrible! How can such a thing be allowed to happen?’ to which the short answer is ‘Burası Türkiye’ – a popular phrase meaning ‘This is Turkey.’ The longer answer, inevitably, comes under the category of ‘It’s complicated’, and I’m not sure that I can provide an adequate explanation. However, the answer seems to lie in a complex tangle of cultural, political and economic factors.

One view, put forward by Bruce Clark in 'Twice A Stranger' his book about the 1923 Population Exchange between Turkey and Greece, is that for painful historical reasons there is no particular general desire here to preserve the architectural heritage, however picturesque, left behind by what are perceived as the historic enemies of the emergence of the Turkish nation state, the Asia Minor Greeks (with a mirror image of this sad situation being found vis-à-vis the many physical remains – and thus reminders - of centuries of Ottoman rule in what is now Greece).

A Turkish friend of mine here in Ayvalik argues against this view, pointing out that the problem of preserving the physical remains of Turkey’s multiply layered multicultural heritage is a much broader one, and I would tend to agree. As described previously, Turkey is chock full, on a scale quite difficult to comprehend, of the archaeological and architectural remains of earlier civilisations (and I will list them again, as I do so love the litany of their names) -

Hattis, Hittites and Hourrites, Uruartians, Phrygians and Lydians, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks and Trojans, Romans, Byzantines, Selcuks and Ottomans

- amongst others. Many of these sites have never been excavated, and perhaps never will be, because there simply isn’t enough money, in a country which is still developing, so from this point of view a few crumbling Ottoman Greek houses in a small town in the north west Aegean are perhaps fairly minor in the great Anatolian scheme of things.

There is a wider cultural point, however, which seems significant: Turks, on the whole, are not that interested in old houses, and with a few exceptions have little interest in restoring them, much less living in them. This is a sweeping generalisation, but there is empirical evidence to support it. To explain why this is the case we need to take a brief look at the development of Ottoman architecture (Ottoman referring to the period between 1299, when the Ottomans took over in Anatolia from the Seljuk Sultanate of Rūm, and 1923, when the Ottoman Empire officially ended and the Turkish Republic was established).

Stephane Yerasimos, an architectural historian specialising in the Ottoman era, describes how Turkish domestic architecture developed using a material – wood - chosen for its transience, with the spiritual symbolism that entailed, in contrast to the permanence of the stone used for public buildings:

'The need to emphasise the transitory character of human life, in every undertaking related thereto, became a fundamental principle of Ottoman civilization, especially in the synthesis it effected between architectural creation and its materials. By contrast with the mosque and other public buildings (caravanserais, baths, hospices etc) , designed to endure and thus fashioned of stone for all eternity, the structures for sheltering the private lives of individuals are in wood, made to be rebuilt from one generation to the next.’

Stefane Yerasimos, ‘Living in Turkey’

The high density and proximity of the wooden houses of Istanbul and other Ottoman cities led to repeated destruction by fire, and gave a wood-built house a life expectancy of only thirty years or so; as a result, the constant replacement of domestic living spaces, generation upon generation, has been a feature of Turkish life for hundreds of years.

It is instructive in this context to consider what has happened during the last hundred years to the wooden houses of Istanbul, the main component of the city’s domestic architecture since the 16th century.

Their fate has some parallels to the situation in Ayvalik. At the beginning of the 20th century most of Istanbul's housing stock consisted of wooden houses. Today, there are only about 250 timber houses left in the entire city, and many of them are in a very poor state of repair.

For four hundred years, wooden houses were built, and regularly replaced, generation after generation. But after particularly devastating fires during World War One, construction in wood was banned by the authorities. The wooden houses could no longer be replaced, and throughout the twentieth century those remaining have fallen victim to neglect, poor planning, and population changes.

Most of the tradesmen who had the skills to maintain and restore these houses were from the Greek and Armenian ethnic minorities who vanished from Anatolia, through death or deportation, during the cataclysmic events of the first two decades of the twentieth century. After the Second World War the Turkish middle classes abandoned the neighbourhoods of decaying wooden houses for more modern suburbs, leaving the old houses to rural immigrants without the money, or the know-how, to repair and maintain them. Although the planning laws in theory protected the houses, as in Ayvalik, many have been allowed or even encouraged to fall down by owners with no interest in preserving them, and local authorities are reluctant to spend public funds on houses in private ownership.

In Ayvalik, too, owners of old decaying houses have preferred to move to more modern accommodation in the suburbs, rather than bear the considerable financial costs of modernising and maintaining inconvenient old houses. Many of the houses in the old town of Ayvalik are now rented, to recent migrants from the east of Turkey, who, like their counterparts in Istanbul, have neither the money nor the skills to maintain the buildings.

It would be possible to obtain funds for the urban regeneration of Ayvalik from the EU, or UNESCO, as has happened in a few other places in Turkey, notably Safranbolu and Eskişehir. However, that would depend on energetic project leadership from the political leaders of the town, something that has to date been notably lacking.

The houses that have been properly restored belong mostly either to incomers from Istanbul or Ankara – Ayvalik attracts writers, artists and musicians, like my neighbour the rock star – or to foreigners, like myself. Unfortunately, there aren’t enough of them and, even more unfortunately, two years ago the Turkish government passed a law banning foreigners from buying property in Turkey in areas of ‘cultural and historical importance’; the old town of Ayvalik is one of those areas. Since there are rather more foreigners than Turks interested in buying these houses, and willing to pay the considerable costs of restoring them to the required standard, this has slowed down the rate of house restoration considerably. A few foreigners continue to buy here by having the ‘tapu’ (property deed) held by a Turkish friend, but it is something not many people are willing to consider.

It is probable that the law will be rescinded at some point, but the houses are fragile, and every winter the torrential rains, which intermittently fill the steep streets of Ayvalik with running water, further damage and destabilise these already weakened structures. At least half a dozen houses have fallen down in the two years I have been living here, and there are many others on the verge of collapse. It is immensely saddening to see the decay progressing, week on week, month on month, year on year.

The ruined houses of Ayvalik have a peculiar, haunting sadness about them. The restored and modernised houses, the lived in houses, have moved on into a new era, and are continuing to function, the horrors of what went before papered over with another layer of history. For the ruins, however, there is no such effacement of the past: they stand there empty, untouched and unlived in for nearly ninety years now, and decaying more with every winter’s rains. And their doors - if they still have doors - stand always open, waiting patiently for their lost owners to come home.

‘The sigh of History rises over ruins, not over landscapes’

Derek Walcott

Wonderful post Hocam - you get to the heart of the reasons for the continued decay.

ReplyDeleteThank you, Sonja.

ReplyDeleteJust realised I forgot to mention one of the complicating factors, which is that the houses now are often owned by the grandchildren of the people who come here in 1923, which means that the ownership of any given house may be split between a number of people, which often makes it very difficult for them to be sold.

Do you have before and after pictures of your home and camel barn? :)

ReplyDeletethis is another great blog post. yet, i still cant see the pictures :(

ReplyDeleteI discovered your blog via paraschos. I am also originated from M.Asia, my father was borned in Isparta and came in Greece in 1922. I visited this city recently. I just send you the url of my blog about Salonica, photos I took during my studies there without understanding what happened to them, during the seventies.

ReplyDeleteThe text is in greek, I don't manage englishso weel and I am columnist in a greek newspaper, but I hope you will like the photos.

Betweenthe old houses you can find turkish houses and jewish houses. Jewish people were almost exterminated during the nazi occupation. They were the main population in the city before that

http://annadamianidi.blogspot.com/