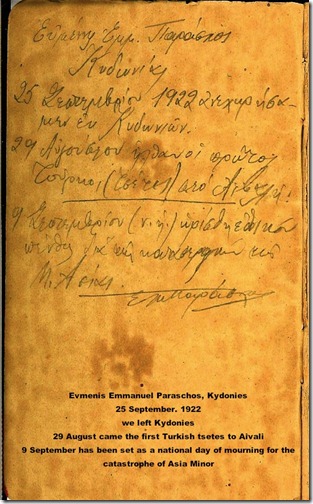

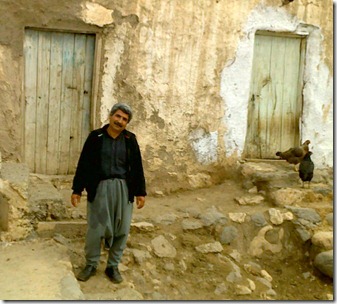

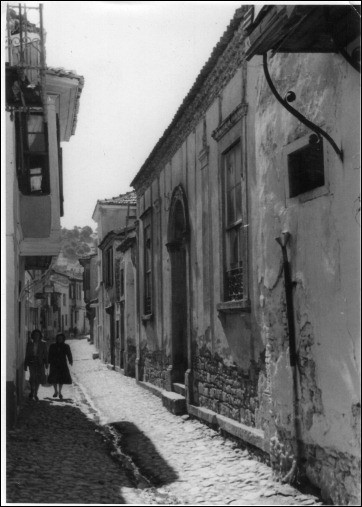

The story so far: A few weeks ago I was contacted by Manny Paraschos, a descendant of one the Ottoman Greek families exiled from Asia Minor in 1922, who asked me to help find their lost family home, somewhere in the old town of Ayvalik (pictured above). There was very little information to go on, and my early attempts to trace the address of the family home from census or property records were unsuccessful, but eventually Manny found and sent to me a photo which was thought to be of the family house. The photo was of very poor quality, the old town in Ayvalik is very big, and many of the old houses are in ruins, but there was an unusual architectural feature in the photograph which reminded me of a street in which I recently had been taking photographs. So, late at night, I went out with my dog Freddie to see if we could find the Paraschos house. Now read on…

It was just after midnight on a warm Aegean evening when Freddie and I set out to find the sokak (street) where there was an unusual window resembling the one in the photograph just emailed to me by Manny Paraschos. It would have been more sensible to do this the following morning, in daylight, but I simply couldn’t wait to see if the street I was thinking of was the right one. I had printed out a copy of Manny’s tiny photograph -

- and was clutching it in my hand as Freddie and I wandered around the maze of streets in the lower part of the town, close to the sea front, looking for the sokak in which I had been taking pictures a few days previously.

Ten minutes later, I found it.

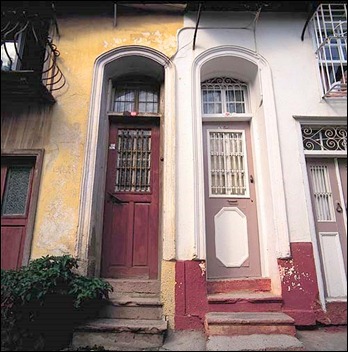

There was the house with the low protruding window, and there was the low one storey house opposite it, with two huge windows framed in the soft, dusky pink local stone. The sokak was well lit, and I stood there in the same position relative to the two houses as Manny’s father had done when he took the photograph on his brief return visit to Ayvalik in 1952.

I looked at the photo, and then I looked at the street; I looked at the street, and then I looked at the photo. Were they the same? I thought they might be, but I wasn’t sure. I took some photographs to send to Manny, from an angle as close as possible to the perspective of the original photograph -

- and then, while Freddie happily sniffed his way up and down the sokak, and started chewing on something that I didn’t care to examine too closely, I walked up closer to the two houses to compare, as best I could, their features with those of the houses in the Paraschos photograph.

The window sticking out on the house on the left certainly looked very similar in height, in the distance it protruded from the house, and in the little roof which covered it. There was nothing that seemed different from the photograph.

The house on the right, however, the house that might or might not be the Paraschos house, had both similarities and differences to the photograph. The two huge windows, framed in stone, seemed identical on the house in front of me and on the house in the photograph. But there should be a door between them, and on the house in front of me there was no door.

Where was the door?

Its absence was not too worrying, because where there are two enormous windows like that on the ground floor of houses in Ayvalik, there is always a door between them. Or there was, once. Many of the old Greek houses have been considerably altered over the last 90 years, and those alterations often include filling in and plastering over windows and doors.

And so it was with this house. When I walked up close to the house, and stood midway between the two windows, I could see quite clearly, under the plaster on the wall, the outline of where the doorframe had been. There were a few other minor differences, all of which could be accounted for by alterations and redecorations to the facade of the house over the last 50 years, but the underlying structure looked very similar indeed.

It seemed to me that there was a fairly strong possibility that this could be the Paraschos house, but I would have to come back in daylight to take some more pictures, and get my friend Erkan to compare the photographs, and come and take a look at the house, and the street. I called to Freddie, and we walked home through the dark, quiet streets. It was past one o’clock in the morning by the time we got in, but I immediately downloaded the photos and sent them to Manny in Boston, with a rather excited email explaining that I thought I might have found the house, but this would need to be confirmed the next day.

And then I went to bed, with the feeling of a job well done.

The following morning I returned to the sokak and took more photographs of the house. In the daylight you could see that the roofline of the street beyond the house mirrored that in the original photograph: a line of one storey buildings, with a much taller house further on. Standing there, looking down the street, and comparing what I could see in front of me to the annoyingly small and dark photograph, I was 90% sure that this was the right house. Now it was time to see if Erkan agreed with me.

I walked the short distance to Erkan’s office, and we compared the photographs on his computer: the tiny, dark, photograph from 1952, and the larger, clearer photograph I had taken earlier that morning.

‘What d’you think? Could they be the same house?’

‘I think they definitely could be’, said Erkan. ‘The streets and the houses and the spatial arrangements are very similar. If it’s not the same place, then there are a hell of a lot of structural, geometrical and proportional coincidences. But….’

Oh dear. What was the ‘but’ going to be? I really didn’t want to be hearing any ‘buts’ right now. I wanted this to be the right house, end of story, so we could all pack up and go home.

‘…but it would be a lot easier to tell if they’re the same house if the old photograph was enlarged, so you could see a bit more detail. Have you tried that?’

At this point I must apologise to the more technically savvy of you, who must have been screeching

‘Enlarge the photo, you idiot! ENLARGE THE FRIGGING PHOTO!’

at the computer screen for some time now, in the manner of children at the pantomime shrieking ‘Look behind you! Look behind you!’

My brain is hardwired for words, pretty much to the exclusion of all else; a corollary of this is that both my visual sense, and my ability to manipulate images on the computer are, unfortunately, somewhere on a par with my skills at using scissors and at piloting moving vehicles of any description through space in accordance with predetermined and seemingly arbitrary rules (but hey, I’m left handed, and I still maintain the Cycling Proficiency test was rigged. We won’t dwell on the driving test: the burning shame of being overtaken by that milk float still lingers, all these years later) .

After receiving the photo the previous day, I had saved it in Picasa (the only photographic software on my computer), which remains almost entirely mysterious to me, other than as a filing system of inordinate complexity. I did try to zoom the picture, but when the image increased in size it just went all fuzzy, and you couldn’t see anything much, so I gave up and forgot about it. It didn’t occur to me that by using different software it might be possible to get a different result.

In fact, since the photo had arrived by courtesy of Gmail, all we had to do

- OK, all Erkan had to do, if you want to be picky about it -

was click ‘view’ instead of ‘save’, whereupon Google helpfully enlarged the tiny old photograph, without it going fuzzy - so clever! – thus immediately revealing a great deal of previously unseen detail.

And the very first thing we saw was that at the end of the street, the pine woods on the hills behind Ayvalik were clearly visible, which they are most certainly NOT from the sokak in my own photograph. That street was much too low down, too near the sea for the woods to be visible at the end of it. It was immediately apparent, even to my undiscerning eye, that the lie of the land, the triangulation between the sea, the hills behind, and street location was way off in my photograph. The house I had found was, quite definitely, the wrong house. No question about it.

‘Oh, BUGGER!’ I said, not for the first time that week.

We were back to square one in the search for the Paraschos house.

Again.

Dismayed, I slumped back into the chair, defeated once more by this seemingly impossible quest. Meanwhile, Erkan did what all Turks do at moments of crisis: he called for some tea. In the shops, offices and restaurants in the centre of Ayvalik they don’t make the tea for clients in-house – it comes from the nearest çay ocağı (tea shop or, more acccurately, ‘tea stop’; an otobus ocağı is a bus stop). Walking through the town you often see men or boys carrying glasses of tea, on metal trays with domed handles, back and forth between the çay ocağıs and their customers in the surrounding buildings.

(In Turkish, the plural of çay ocağı is, of course, not çay ocağıs, but çay ocaklar. But somehow that doesn’t work when you’re writing in English, for people who aren’t familiar with Turkish plurals. I will therefore apologise now to Turkish language purists both for this, and for all the other linguistically hybrid and grammatically incorrect sokaks, kedis, lokantas, and bayrams which may be lurking in blogposts still to come.

Mea culpa. Bu Türklish. Çok yanlış, biliyorum. Ben İngilizim. Türkçe çok zor. Çok özür dilerim).

Erkan’s office has an intercom link to the çay ocağı next door, and the tea usually appears within a minute or two of being ordered, as it did this day. While Erkan went off to deal with a customer who wanted to buy a big modern villa next to the beach in Ayvalik’s smart suburb of Şirinkent, I stirred sugar into the little glass of tea and gazed gloomily at the enlarged copy of Manny’s photo we had just printed out.

You could see much more detail on the enlarged picture:

the way the sokak curved round to the right; decorative stone columns inset on the wall on either side of the door; two more one storey buildings, and then a complete two storey house, beyond the house we were looking at; and, perhaps most importantly, you got a sense of the distance between the house and the pine-covered hills that could now clearly be seen in the background of the photograph.

The old town of Ayvalik is crossed horizontally by three wide roads: Atatürk Boulevard is the main road through the town, running round the bay right next to the sea; about 100 metres inland, beyond the area of old stone industrial buildings which used to be olive oil and soap factories, and now house carpentry, glass and wrought iron workshops, as well as cafes and supermarkets, lies Barbaros Caddesi, a busy shopping street which marks the boundary between the commercial and residential neighbourhoods. The third big horizontal road is 13 Nisan Caddesi, another 400 metres or so closer to the hills, and situated on their lower slopes.

Looking at the enlarged photograph, it was now obvious that the sokak in the picture was located somewhere in the lower part of the town, but not too close to the sea, in the large central residential area bordered by 13 Nisan Caddesi at the top, and Barbaros Caddesi at the bottom. I began to think about how to conduct a systematic search, starting from the northern edge of the old town, and working our way in towards the centre, sokak by sokak, alley by alley, house by house.

If you look again at the photo of the old town at the top of this post, you will get some idea of just how big an area we would have to cover. It would be both labour-intensive and time-consuming, but would offer the best hope of finding the house. If the house still existed, of course, which was by no means certain. I had been very foolish to think that I had immediately identified the house in Manny’s photograph, just from some superficial similarities; Ayvalik was full of houses like that, in sokaks like that.

I cringed, remembering my blithe certainty, the previous evening, of having found the house, and bitterly regretted firing off the email to Manny announcing that his lost family home had probably been found. Finding the house was a matter of great emotional importance to the whole Paraschos family, in America and in Greece; I should have waited until I was absolutely certain it was the right one, before raising their hopes like this. Now I was going to have to send another email to Manny, saying ‘I’m awfully sorry, but...’

Utterly despondent, and furious with myself for having jumped the gun, I had by this time been sitting staring blankly at the enlarged photograph for about 20 minutes. And then, quite suddenly, out of absolutely nowhere, a thought popped into my head:

‘I know this house'.

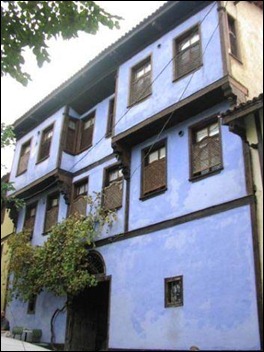

I looked at the big windows, and the great big arched doorway, and the dilapidated plaster on the wall peeling off to show the brickwork underneath; a house not in ruins, but showing considerable signs of neglect.

And then my brain somehow superimposed on that house in the photo another image: of an identical house, with the big windows and the great big door, but replastered, painted, beautifully restored, and with containers planted with flowers standing on either side of the steps.

It was a house in the next street to my own, maybe 300 metres from where I live; close to the corner of Barbaros Caddesi, in a sokak curving round to the right, and with a view of the hills behind. It was a house I had always loved, because in a town so full of ruins, it had been properly restored and was immaculately kept; and although it had clearly lost its upper storeys in the earthquake in 1944, it was still an impressive house, one that you would take a second look at as you walked past, especially when the great big double front doors were open and you could catch a glimpse of the inside, where there seemed to be some kind of courtyard or atrium.

As the two images fused into one in my brain I became convinced that this, truly, was the right house. It had taken me this long to identify it simply because the house today looks very different from the way it did when it was photographed in the 1950s.

And, of course, because of my almost complete lack of visuo-spatial skills.

Despite the growing inner certainty that I was finally on the right track, it still seemed too good to be true. Could it really be the case that of all the houses in Ayvalik, the house in the Paraschos photograph should turn out to be one that I knew well, that was literally just down the road from my own? One seemingly strong candidate for the house had already been proved to be completely wrong; how likely was it that immediately afterwards I would manage to identify the right house, simply by looking at the enlarged photograph?

With the sheer improbability of this in mind, I refrained from leaping up and screaming about this new development to Erkan, who was just saying goodbye to his client; I had, after all, been wrong before. This time I was going to make absolutely sure I was right before getting too excited.

Erkan, on looking again at the enlarged photo and being informed of the location of the house of which I was now thinking, looked thoughtful:

‘Yeah, I know that house. It could be it. Only one way to tell – let’s go and have a look'.

This post is getting much too long, and the hour is very late, but, dear Reader, I have tried your patience long enough already in the slow, circuitous and episodic narration of this story. To make you wait for yet another instalment before I reveal the outcome would be very unkind. And I don’t like getting hate mail.

Are you still sitting comfortably? Right, then we’ll continue.

It’s only a five minute walk from Erkan’s office along Barbaros Caddesi to the sokak we were looking for, but that day it was a very long five minutes indeed. I held the A4 sized enlargement of the photo in my hand and, as we turned into the sokak and saw the house, held it up to compare the two: the dilapidated house of fifty years ago, and the smart restored house of 2010.

It was, without a shadow of a doubt, the same house.

The great big arched door between the windows, with the decorative columns of stone on either side, the curve of the sokak, the neighbouring houses, the window opposite, the view to the hills: all were identical. The only differences from the photograph were those caused by the restoration of the building.

We had found the house in the photograph.

And this is it:

(to be continued)

Coming up next from the Camel Barn Library: ‘An email from a ghost- Part V : Inside the Paraschos House’.

![240820104678[1] 240820104678[1]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/_ZDfm7EUoodI/TLtxd3J2OzI/AAAAAAAAAa0/xjU5ob3MUzg/240820104678%5B1%5D_thumb%5B4%5D.jpg?imgmax=800)