So, there I was, 3 weeks ago, with my shiny new notebook and a blue Pilot 0.5mm fine point pen, but not exactly sure what, if anything, I was going to do with them. I had no real idea whether Project Paraschos would actually turn into something justifying the acquisition of new stationery items, or if my newly-commenced quest to find the location of the ancestral home of the Paraschos family ( formerly of Ayvalik, now of Boston and Athens) was going to end in a ruin full of feral cats, a newly concreted car park (of which there are many in Ayvalik, on the sites of old houses) or a complete dead end.

I walked down town to meet my friend Erkan -

(We are getting ahead of ourselves here, because Erkan is an important person in the story of the Camel Barn Library, which I am writing here chronologically, and needs to be introduced to you properly. But this is a real time addition to the story, so he is popping up out of sequence. Never mind. He will make his scheduled entrance in the narrative very soon. He is an interesting bloke, who has had a quite extraordinary life.)

- in a cafe by the sea, located in one of the most famous buildings in Ayvalik, at the end of a line of neoclassical facades on the water’s edge which constitute one of Ayvalik’s iconic images, frequently displayed on postcards, tourist memorabilia, or illustrating writing about the town, as above.

I was quite excited, as I walked into the cafe and saw Erkan waiting for me, because I thought my idea about finding the Paraschos house through census data was going to be a winner. I am familiar with population censuses, as they are part of my field of academic interest, and that morning had done a little research on censuses carried out during the time of the Ottoman Empire.

Censuses were first conducted in the Ottoman Empire, as they were in England, during the first half of the 19th century. The first modern census took place in 1828/29 in both the European and Anatolian parts of the Ottoman Empire. Its main purpose was to provide quantitative data to facilitate the levying of personal taxes on non-Muslims, and the conscription of Muslim male adults into the army.

In the 1830s the Ottoman government established the Office of Population Registers (Ceride-i Nüfus Nezareti) as part of the Ministry of Interior, and censuses in various different forms were conducted at irregular intervals until the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. The last one took place in 1905, and this was where I hoped to find the information we were looking for, not in the published data giving the macro view of the census, but in the detailed unpublished census data in which, as in the British censuses, individuals are located to street addresses; each person’s name is recorded against the exact address at which they live.

Unpublished census data in the UK from 100 years ago and before is now available on the internet via the National Archive, and is searchable by name and location. I have done some genealogical research on my own family using these databases, and it was remarkably easy. I didn’t really expect to find that the entire final Ottoman Empire census of 1905 would be available at the click of a mouse – this is Turkey, after all – but was hopeful that if we could get access to the unpublished census data for Ayvalik, a relatively small town, somewhere in those data we should be able to find, if we looked hard enough, the street and house number of the Paraschos family house.

I bounced into the cafe, ordered a glass of çay (tea), and related to Erkan both The Story So Far, and my idea for finding the Paraschos house using census data. What did he think?

Even before he opened his mouth, the expression was on Erkan’s face was not encouraging. Why?

‘You’re forgetting the language’ he said.

‘What do you mean, the language?’

‘Everything written during the time of the Ottoman Empire was in Ottoman Turkish. I couldn’t read it. Nor could you.’

My heart sank. In my excitement about the census idea, I had completely forgotten one very important fact: that one of the many sharp disjunctions between the Ottoman Empire of before, and the Turkish Republic of now, is in language. The modernisation of the Turkish language was one of the many fundamental reforms instituted by Mustafa Kemal, later Ataturk, the father of modern Turkey, as he separated the squalling infant of the new Turkish Republic from its dying progenitor, the Ottoman Empire.

You may be wondering how a language can suddenly be modernised out of all recognition without the entire population becoming extremely confused, and why anyone should wish to do such a thing, so let us digress for a moment into the history of the Turkish language.

During the six centuries of the Ottoman Empire’s existence the Turkish language used within its borders developed into two distinct variants, with different uses: first, there was the simpler, purer, vernacular form of Turkish, ‘kaba Türkçe’ or ‘rough Turkish’ spoken by the lower echelons of society, which remained close to the original form of Turkish brought into Anatolia from Central Asia by nomadic Turkic tribes in the late Middle Ages, namely Oğuz ( Oghuz) Turkish.

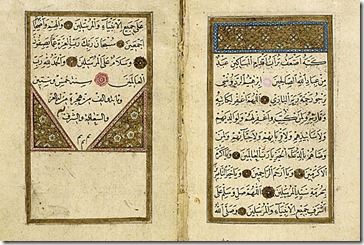

Second, following the adoption of Islam in 950 AD, and in tandem with the growth of the initially small Ottoman principality into an empire, there developed Ottoman Turkish, which eventually became the literary and administrative language of the Ottoman Empire, in particular between the 16th and 19th centuries.

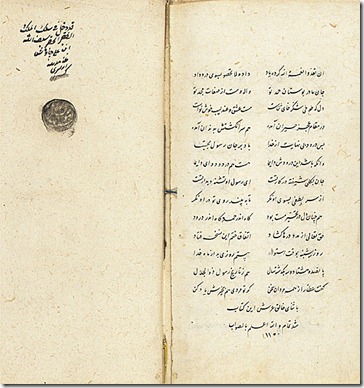

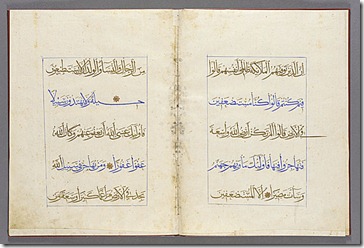

Via the Persians, who introduced them to Islam, the Turks were influenced by Arabic, the language of the Koran. This, plus the fact that the Arabs and Persians were then advanced in science and literature, led the Turks to adopt the Arabic alphabet, although not its grammar. Ottoman Turkish thus came to contain a vast amount of loan words imported from Arabic and Persian, was written in a variant of the Perso-Arabic script, and was an elaborate, ornamented, rhetorical language, in large part unintelligible to the mostly illiterate majority of the population, who spoke vernacular Turkish: Ottoman Turkish was used by only about 9 percent of the population.

And this is what it looked like…

In an earlier post we discussed the triune nature of the human brain, with its newer, reasoning part, the neo-cortex, welded awkwardly on to its older, much more primitive parts, the limbic and reptile brains, and concluded that if you were if you were setting out to design a brain for a thinking being, it certainly wouldn’t be constructed like this.

Ottoman Turkish was the linguistic equivalent of the human brain: a language welded together from quite disparate parts which did not function well together, and challenging to use, even for those who were well acquainted with it. Trying to combine Turkish , Persian and Arabic together in one language was really never a good plan: the grammar and morphology of the three languages were quite at odds with one another.

As the multi-cultural Ottoman Empire declined, and there developed in Anatolia a strong movement towards an ur-Turkishness, and a Turkish nationalism which would culminate in a modern Turkish republic which expelled ‘foreign’ minorities, the strange hybrid language of Ottoman Turkish became a symbol of what needed to be left behind, and the momentum grew for the language to be reformed into something truer to its original old Turkish roots, and more accessible to the wider population.

There were early attempts to get language reform under way in the late 19thC, but the major change came a few years after the founding of the new Turkish Republic in 1923, when Atatürk instigated the great language reform. This had two major parts: one was the elimination of Arabic and Persian words from the language, and their replacement with words from old Turkish and, if necessary, neologisms based on old Turkish roots.

The Turkish Language Society was set up to bring back into use authentic Turkish words discovered in linguistic surveys and research, and its work continues to this day. The outcome of these linguistic reforms, according to the Turkish Ministry of Culture, is that the use of authentic Turkish words in written texts has risen from 35-40 percent in 1932, to 75-80 percent in recent years.

The other part of the reform was changing the script in which Turkish was written from the Arabic alphabet to the Roman, adapted with a few extra letters to accommodate Turkish vowel sounds. Atatürk strongly believed that for Turkey to become a modern state, a contemporary civilisation, it was essential to benefit from Western culture. The change to the Roman alphabet in 1928, which allied Turkish with European rather than Oriental languages, was thus a deliberate and highly symbolic act, one of the key points in his extraordinarily comprehensive programme of political, social and cultural reforms (of which we will discuss other aspects in due course), which dragged Turkey into the modern world, laying the foundations for the successful modern state which exists today.

Atatürk himself promoted the change by touring the country to introduce the new alphabet to the public, as in the photograph below, taken in Sinop -

- and public education centers opened throughout the country, resulting in a dramatic increase in literacy, which before the language reform was about 9%. By 1950, literacy rates had risen to 48.4% among males and 20.7% among females.

All exciting and important stuff, but what the language reform also did was to cut modern Turkey off, suddenly and sharply, from direct access to its written past, from the extensive written records of the Ottoman Empire, from its literature, and from its recent history. Atatürk gave a famous speech in Ottoman Turkish to the youth of the nation in 1920, one that is still compulsory reading for all Turkish school-children, but in its original version the speech is now unintelligible to the reader of modern Turkish, even if transliterated into Roman script.

Every couple of decades Atatürk’s speech has to be retranslated, so that succeeding generations can understand it. The language has changed, and is continuing to change, that much. By analogy, imagine if the English language had changed so much that Winston Churchill’s ‘Blood, sweat and tears’ speech of 1940 had to be periodically updated with new vocabulary so that we could continue to understand it. For a young Turkish person now, trying to read the original text of Ataturk’s speech would be like an English person trying to read Anglo Saxon.

And, returning to our subject after a considerable detour, the same problem would arise in trying to read Ottoman census records. As soon as Erkan mentioned the language problem, I realised that my plan was doomed: it would be impossible without the assistance of a scholar of Ottoman Turkish. And the chances of finding in Ayvalik an Ottoman Turkish scholar who would be prepared to go through the town’s entire census records to find the name ‘Paraschos’, just for fun, seemed vanishingly small.

Erkan then put an end to the whole idea by explaining that anyway, all records in Ottoman Turkish were now held in a national archive in Ankara, so we wouldn’t even be able to access them without making a 400 mile trip.

‘Oh, BUGGER’ I said. ‘Well, that’s that, then.’

We ordered some more tea, and I tried to regroup. Time to move on to Plan B, which was to go to the local property records office, and look at records from pre-1922 which would …… yes, which would also be written in Ottoman Turkish.

Plan B was then disposed of even more swiftly than plan A, as Erkan explained that current property records here only go back to the early 1930s, when the houses of Ayvalik were registered, with their new owners, in modern Turkish; all the older records were also in the national archive in Ankara.

Project Paraschos was turning out to be much more difficult than I had anticipated. There seemed to be no way forward without some more information, some clue, from the Paraschos family itself. Manny had told me he was searching through his late father’s papers to see if he could find any more information, and it was thought that his elderly aunt, who was away from home at the moment, might have a photograph of the house.

I mentioned the possible existence of a photograph to Erkan who is, amongst other things, an estate agent. His face brightened.

‘That would be much, much easier.’ he said.

‘I know every street, every house in this town. If they send a photo, and the house is still standing, I’ll be able to find it. I promise you.’

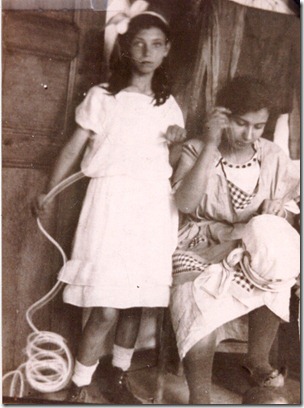

I agreed to keep him updated on any developments, went home and sat down at my computer to send Manny an email telling him of the disappointing outcome of my first attempt to find the house. When I opened my inbox, I saw that there was a new email waiting there for me from Manny. Even without opening it, I could see that there was an attachment to the email. A photograph.

I opened up the email and began to read.

(to be continued)